In 1982, a letter arrived at Hospice of the Piedmont’s office addressed to “The Hot Spice of the Piedmont.”

It wasn’t a prank. It was simply a reflection of how unfamiliar the word “hospice” still was to most Americans at the time.

Today, hospice is part of mainstream healthcare. But back in 1980, it was a radical idea, often misunderstood or unknown altogether. As we celebrate 45 years since the founding of Hospice of the Piedmont, it’s the perfect moment to look back and see how far we’ve come.

—

—

A New Idea, Born Out of Old Needs

The roots of modern hospice care trace back to 1967, when Dame Cicely Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice in London. Saunders believed that dying was not just a medical event, but an essential part of the human journey—and that patients deserved not just treatment, but dignity, comfort, and emotional support at the end of life.

Her approach inspired the birth of hospice programs around the world. In the U.S., one of the first sparks came when Saunders visited Yale in the 1960s, inspiring healthcare leaders like Florence Wald, who would go on to establish the Connecticut Hospice in 1974.

Fast-forward to October 4, 1978, when Saunders came to speak at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. That visit planted a seed that would soon grow into Hospice of the Piedmont. Among those in the audience was Adge Coburn, a retired nurse who had lost her daughter to cancer. Coburn understood firsthand how important hospice care could be—and how urgently it was needed in Central Virginia.

—

—

May 28, 1980: It All Started in a Living Room

According to R. Tal Haynes’ Sharing the Journey: The First Thirty Years of Hospice of the Piedmont, thirty people crowded into Adge Coburn’s living room outside Charlottesville on May 28, 1980. There was no official office, no Medicare reimbursement, and no playbook for how to build a hospice. What they had was a vision: a local, volunteer-driven program that would help patients and families face the end of life with dignity.

That first meeting became the official founding of Hospice of the Piedmont.

Their early work focused on training volunteers, raising donations, and simply getting the word out about what hospice even was. (Clearly, there were still some communication challenges—the “Hot Spice” letter showed up just two years later.)

Still, they pressed forward.

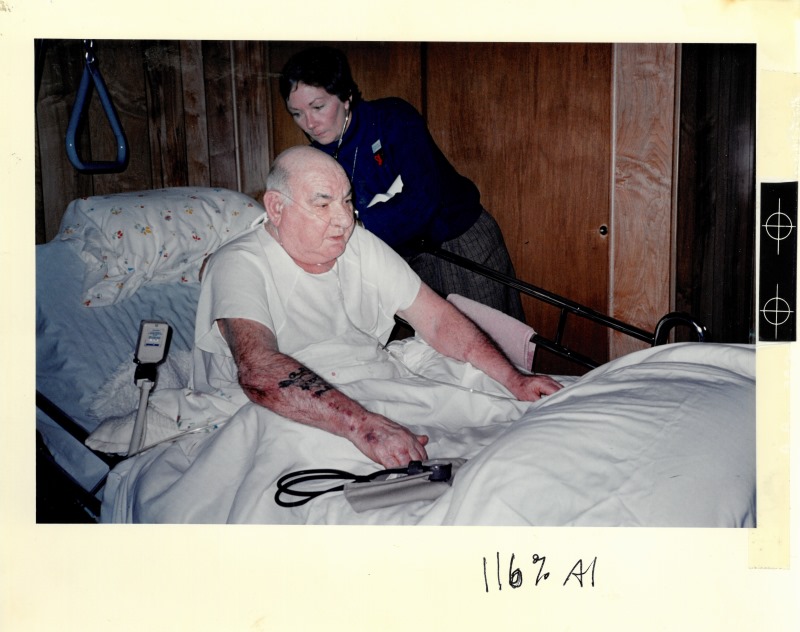

Within the first year, Hospice of the Piedmont had accepted its first two patients: a father of eight and a mother of a young daughter. Care was provided mostly at home, with volunteers delivering up to 18 hours of support a week. Medications, medical supplies, and visits from public health nurses were arranged through pure determination and a patchwork of local support.

—

—

A Movement Still Finding Its Voice

While Adge Coburn’s living-room team was figuring out how to provide care, the broader U.S. hospice movement was wrestling with the same challenges—money, policy, and public perception.

-

Grassroots First, Government Later

Hospice in 1980 was not a federal program. Senator Edward Kennedy captured the mood in 1978:

“The hospice movement is a great movement—not because it was legislated by Congress, or mandated by the Federal Government, but because it evolved out of the hearts of people who care.”

Policy was barely catching up. Medicare’s hospice benefit wouldn’t launch until 1983, and even then, only as a three-year trial.

-

A “Death-Denying” Culture

Before hospice, death was something to hide, often behind hospital curtains or nursing-home doors. Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross called this out in her 1969 bestseller On Death and Dying, arguing that society “institutionalized and isolated” the dying. Her bluntness cracked open a previously taboo conversation.

-

Low Public Awareness

Most families in 1980 had never heard the term “Hospice.” Activists scrambled to explain:

1979 – Short film “Hospice: An Alternative Way of Care for the Dying.”

1982 – A PSA featuring actor Jack Klugman airs nationally.

Even so, misunderstandings lingered—hence that “Hot Spice” letter.

-

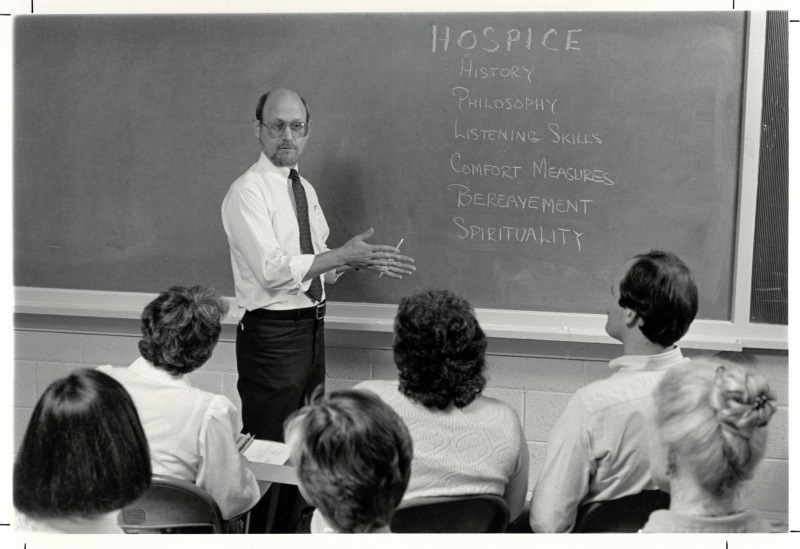

Mixed Reception in Medicine

Forward-thinking physicians and nurses embraced hospice early, but many peers worried it meant “giving up.” Hospice of the Piedmont’s first executive director, Dinah Ansley, recalled “countless talks I gave educating the public and physicians about hospice philosophy.” Over time, data showed hospice controlled pain, reduced hospital readmissions, and left families more satisfied—slowly changing medical minds.

—

—

The World of Hospice in 1980: A Different Planet

Today, hospice is part of the standard healthcare conversation. In 1980, it was anything but. Here’s a snapshot of what hospice care looked like when Hospice of the Piedmont was founded:

| 1980 | Today |

| Fewer than 100 hospices existed nationwide | More than 4,700 hospices |

| Less than 1% of people who died received hospice care | About 50% of Medicare deaths occur in hospice |

| No Medicare benefit for hospice (passed in 1982, active in 1983) | Standard Medicare and Medicaid coverage |

| Hospice was seen as radical and often misunderstood | Hospice is widely recognized and trusted |

| Programs operated primarily on volunteer labor and donations | Combination of insurance reimbursement and philanthropy |

Without Medicare or insurance payments, early hospices—like HOP—relied entirely on charitable donations, community goodwill, and pure volunteer grit. Nurses often worked without pay. Volunteers raised money, sat with patients, taught family members how to manage care, cooked meals, or helped with errands.

—

—

Why Hospice of the Piedmont Endured

Many early hospices didn’t survive the 1980s. Hospice of the Piedmont did—and continues to thrive—because of a few enduring principles:

-

Community Focus

From the start, Hospice of the Piedmont belonged to Central Virginia, not to a corporate parent or outside investors. Being locally rooted allowed the organization to build trust, respond to community needs, and adapt over time.

-

Mission Over Profit

While the healthcare world has shifted dramatically in recent decades, with many for-profit hospices now in operation, Hospice of the Piedmont has remained nonprofit. Thanks to generous community philanthropy, HOP provides services and programs to support patients and families that other hospices don’t.

-

Expertise and Empathy

From Adge Coburn’s hand-written meeting minutes to today’s interdisciplinary teams of doctors, nurses, chaplains, social workers, and volunteers, HOP has always put patient-centered care at the forefront.

-

A Volunteer Backbone

Even as the organization grew and professionalized, volunteers have remained a vital part of the work. They were the heart of hospice care in 1980, and they still are today.

—

—

A National Backdrop, a Local Legacy

In 1980, hospice in America was an experiment—compassionate, underfunded, and occasionally misspelled. Government policy lagged. Public awareness was minimal. Yet the grassroots insisted on something better at life’s end, and Hospice of the Piedmont was early on that front line.

What began in Adge Coburn’s living room mirrored the national story: volunteer-led beginnings, financial cliffhangers, gradual recognition, and, finally, a place in standard healthcare. The concept proved itself on a small scale and was poised for mainstream adoption, thanks in part to pioneers here in Central Virginia.

Forty-five years later, hospice is an integral part of U.S. healthcare, and Hospice of the Piedmont is still nonprofit, still local, and still guided by the same conviction: expertise and empathy, delivered wherever patients call home.

—

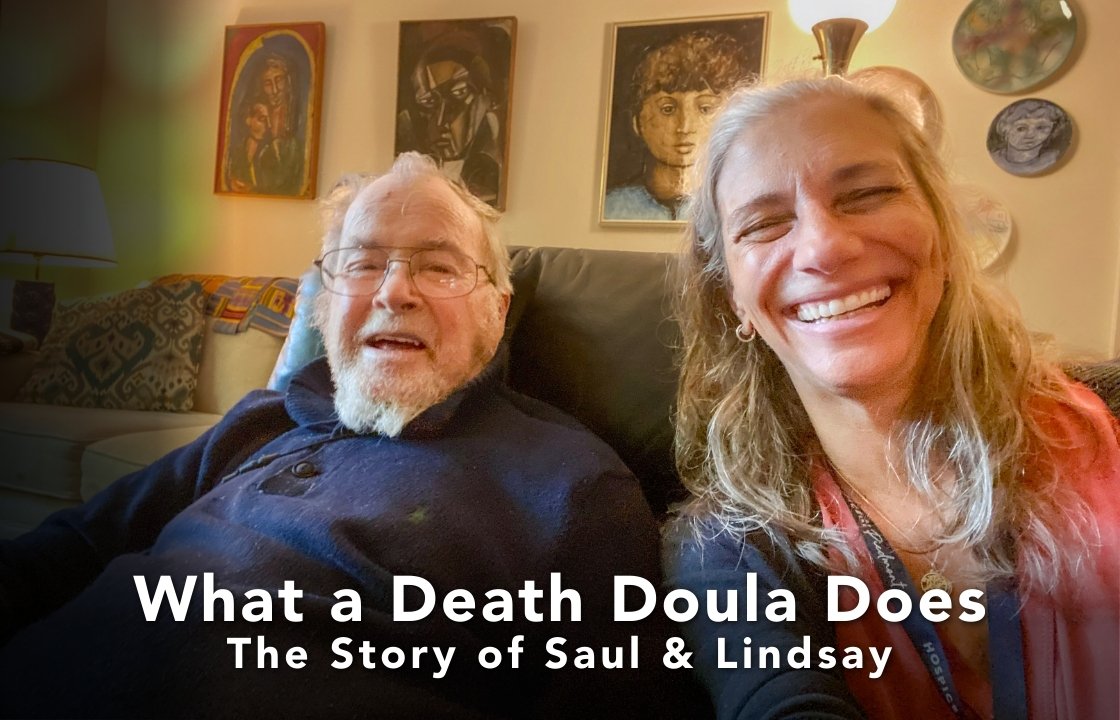

Note: If you recognize anyone in these photos please write to transformations@hopva.org so that we can update our archives.