Marianne grew up in Buffalo, New York. In 1966, she and two friends enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps together through what was known as the “Buddy System.”

“We were guaranteed to be assigned together, which doesn’t always work out, but it did for us. We went to Basic together, and then we were at the same hospital in Vietnam,” she says.

The three young women had all grown up in big families. “We all had brothers in the military. I had three. And we were inspired by them. Plus,” she adds with a laugh, “we went to see the world. Ha ha.”

They trained at Fort Sam Houston in Texas, the Army’s central training post for medical personnel. When it was time to deploy, the local news came to cover their departure. “So Buffalo knew there were women in Vietnam,” Marianne says. “They saw us. My friends were televised getting on the airplane.”

“I didn’t realize I was at the beginning.”

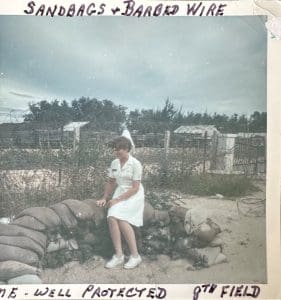

At the time, the Vietnam War was escalating rapidly. Marianne arrived in-country in September 1966 and was stationed at the 8th Field Hospital in Nha Trang—a 100-bed facility that was, at that point, still under construction.

“I didn’t realize I was deployed at the beginning conflict,” she says. “The 8th Field was the only hospital the Army had in Vietnam at that point.”

The work was immediate and intense. “We worked very long hours. Six days a week, 12 hours a day—or more depending on what battles were occurring and how many casualties were coming in.”

Outside the hospital, Marianne and other medics volunteered in nearby villages through the Army’s Civil Action Program. “We’d hop on this big deuce-and-a-half truck—this humongous truck—and we went to the villages to provide care to the civilians,” she says. “We took care of the wounded, gave immunizations, and bathed some of the kids. The children were overjoyed when we handed out sweet treats.”

“We dated that way.”

She also met someone.

It was at Basic Training, months earlier, that Marianne had first met the man who would become her husband. He was an officer in the administrative branch of the Medical Service Corps, tasked with managing the medical units and coordinating the transportation of the wounded.

Though initially assigned to the same hospital, his orders were changed before he arrived. Later, while she was stationed at the 93rd Evacuation Hospital near Saigon, he arrived at her location by flying in on Medevac helicopters.

“We dated that way,” she says.

Eventually, he proposed—at the 93rd Evac in Biên Hòa on a bridge over a drainage ditch built for monsoon season.

“We’ve been married for 56 years.”

“Much too quiet.”

After a year in Vietnam, Marianne returned to the U.S., but adjusting to life Stateside proved more complex than expected.

“One thing I remember about coming home: We were aware of protests, but they weren’t as widespread when I left Vietnam in September 1967,” she explains.

“Even the nurses would take off their uniforms on the plane before we landed on American soil. We’d board the plane in our uniforms in Vietnam, and then we’d change into civilian clothes before we landed. We were kind of forewarned,” she says. “That was quite an experience.”

Civilian life came with other changes.

“It was much too quiet,” she says. “Because we were used to hearing bombs and rockets, and the flares would go off, and sometimes we had to go to the bunkers if there was a threat.”

Her sister told her she moaned in her sleep. Loud noises made her flinch.

“There were no women in Vietnam.”

Professionally, it wasn’t any easier. She thought she’d return to a robust nursing career—especially after the kinds of techniques she’d learned in the field. But civilian hospitals didn’t see it that way.

“Oh, my goodness,” she says. “We’d go to apply for jobs, and they’d say, ‘Oh, you haven’t had real experience. What do you know?’ We weren’t allowed to do the procedures we were trained for.”

And while her hometown had celebrated her departure, the country as a whole did little to acknowledge her return.

“Most everybody said there were no women in Vietnam,” she says. “Even to this day, you don’t see many documentaries… Ken Burns had an excellent one, but for the most part, you don’t see women portrayed. And mind you, we were not drafted; we were all volunteers. So that’s significant.”

“We could finally go there.”

In 1993, Marianne and her husband attended the dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“25,000 people marched,” she remembers. “It was exhilarating.”

At one point, she stepped away from the crowd. That’s when she heard a familiar voice calling her name.

“There was my friend who was part of the Buddy System—one of the three nurses. She saw me. We hadn’t seen each other in many years. It was a shared experience… It’s sometimes hard to define what your feelings are. I was grateful for that. I was glad to see her again.”

The memorial had been a long time coming. “The Vietnam nurse who advocated for it faced years of resistance from Congress,” Marianne says. “She struggled hard. And mind you, this was 1993—and she struggled for many years after over 8,000 of us served.”

“They just clam up, and that’s their right.”

In 2019, Marianne joined Hospice of the Piedmont as a volunteer.

“I’ve often been involved with family and friends at the end of their lives,” she says. “It’s just something I felt comfortable doing.” Now, she visits patients at the Center for Acute Hospice Care.

“I thoroughly enjoy the CAHC,” she says. “I derive a lot of satisfaction and enjoy working with the staff, the patients, and the families. That’s something very close to my heart, and I’m comfortable doing it.”

Occasionally, she visits with Vietnam Veterans at the CAHC. Sometimes, she plays music from their military branch on her phone. Sometimes, they talk. Sometimes, they don’t.

“Some open up; others don’t want to,” she says. “They just clam up, and that’s their right—their right to privacy. So, I just share their experience, and we’re all here to support each other.”

Whenever she sees a Vietnam Veteran hat in public, she stops. “I will always extend my hand and tell them I am also a Veteran,” she says. “And we share stories. Some of them were wounded, so they appreciate what a nurse did in Vietnam. But others have never talked to a female vet. Sometimes, we end up hugging each other.”

“I didn’t talk about it.”

For a long time, Marianne didn’t discuss her own experiences either.

“I didn’t talk about it until someone invited me to speak at a book club about The Women,” she says, referencing Kristin Hanna’s best-selling historical novel about nurses in Vietnam.

“This was just last May. We’re almost at the one-year mark since I shared that experience so deeply. I never did it before. This was after how many years? I left there in ’67. Still, I opened up… and that was a true catharsis,” she says.

Her granddaughters have asked her about her time in the Army. “‘They call me, ‘Oma.’ They interviewed me about my war experience. They’re so cute. They know about it.”

“Welcome home.”

Marianne says she often thinks about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

“There are 58,318 names engraved on the black granite wall in D.C.,” she says. “So when I think of ‘Welcome Home Vietnam,’ I think about how 500 Vietnam Vets are dying per day now.”

Many are in need of hospice care. Some are still unsure if they belong here.

Marianne hopes they know they do.

“They need to know that someone’s interested in their patriotism and what they did for our country,” she says. “We’re all here to support each other.”

At Hospice of the Piedmont, we care for veterans every day. We honor every service story—whether it’s told in detail or never spoken at all. And for Vietnam Veterans especially, we want to say what was too often left unsaid:

You served. You matter. Welcome home.